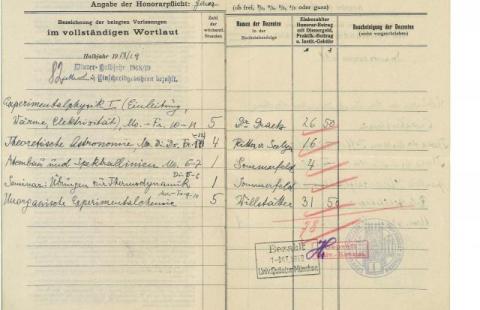

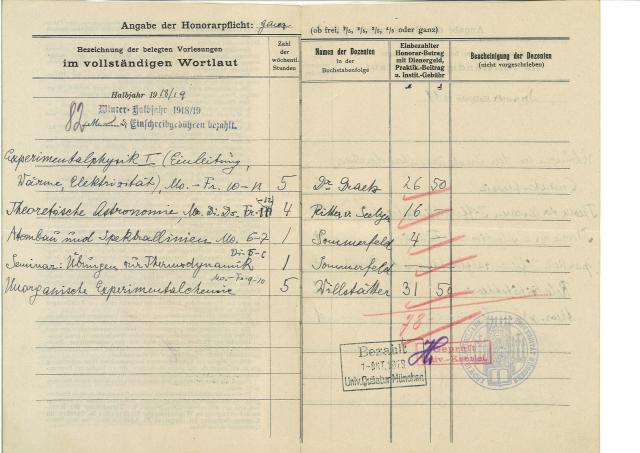

Wolfgang Pauli begins his studies in Munich

In October 1918 Wolfgang Pauli left Vienna to…

Know more

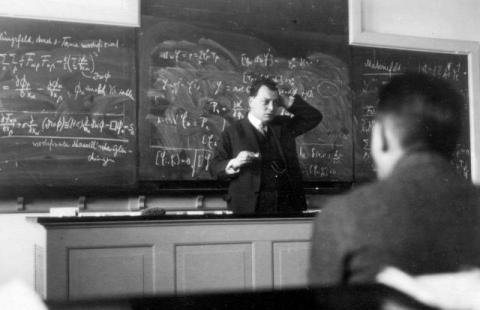

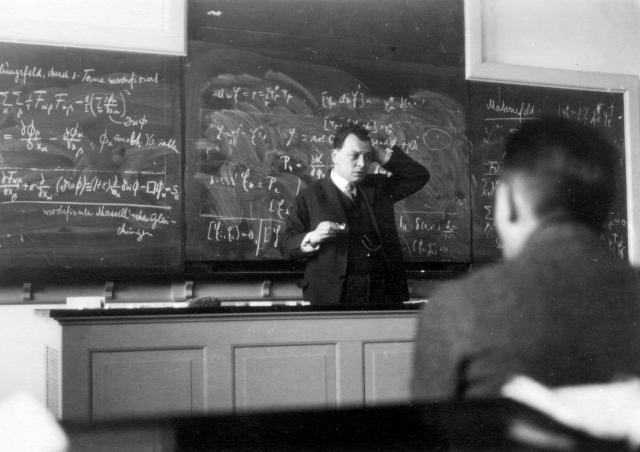

Wolfgang Pauli appointed professor at ETH Zürich

Despite some reservations about his lecturing…

Know more

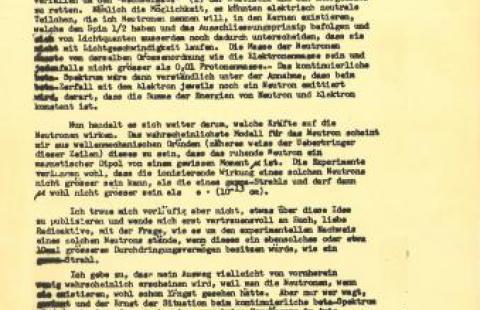

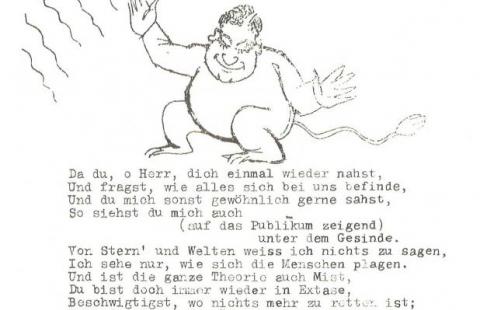

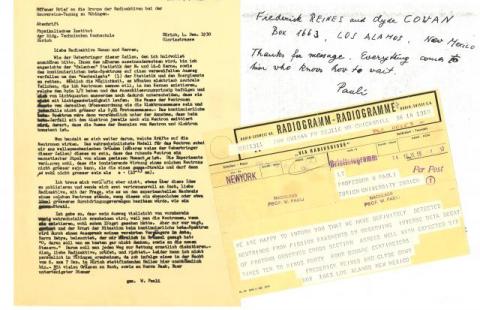

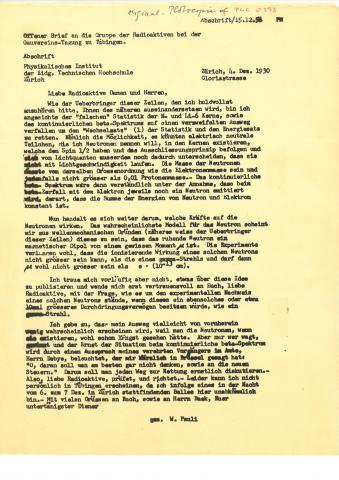

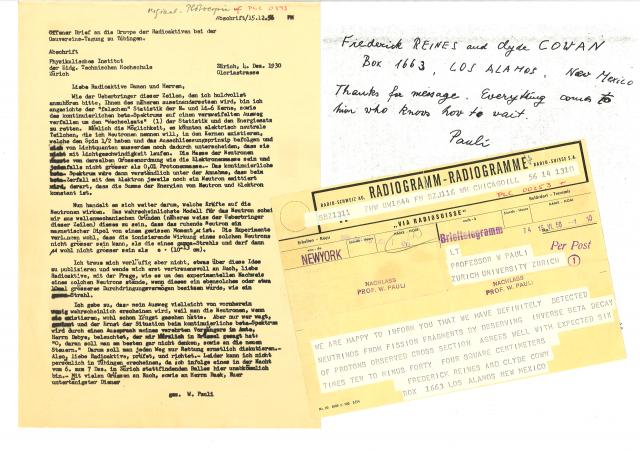

December 1930 - Pauli’s Neutrino letter (now in music and art!)

On 4 December 1930, Wolfgang Pauli wrote his…

Know more

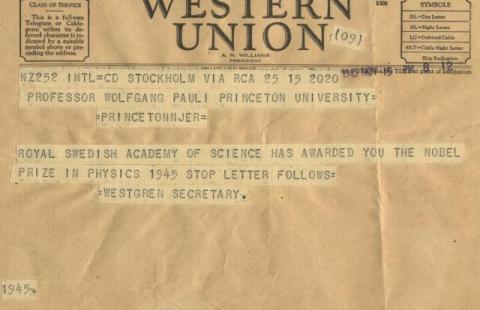

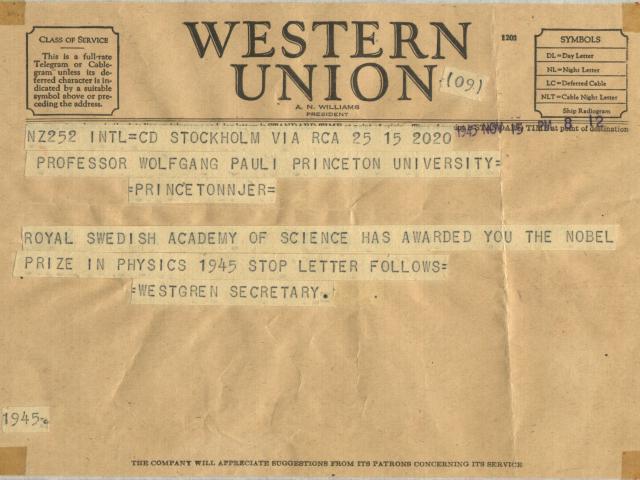

Wolfgang Pauli learns that he has been awarded the Nobel prize

Wolfgang Pauli was awarded the 1945 Nobel…

Know more

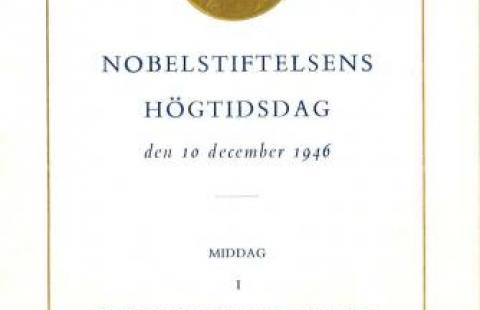

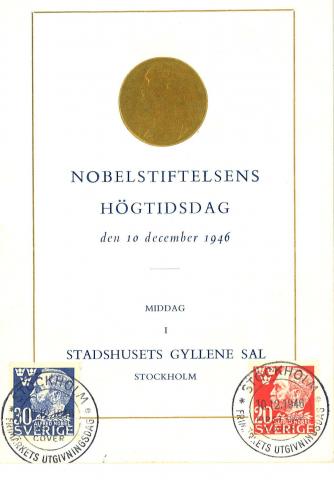

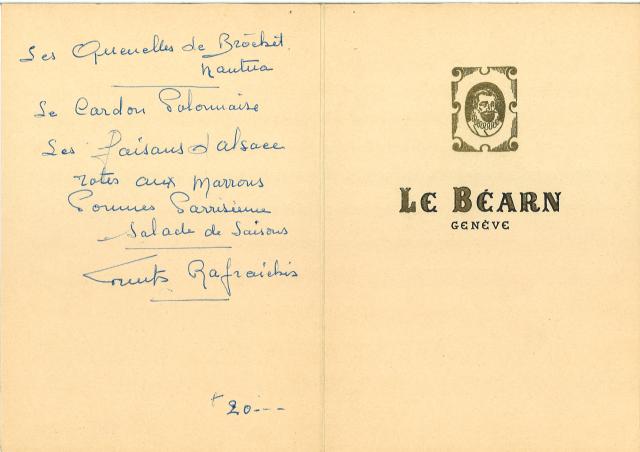

Pauli travels to Sweden to receive the Nobel prize

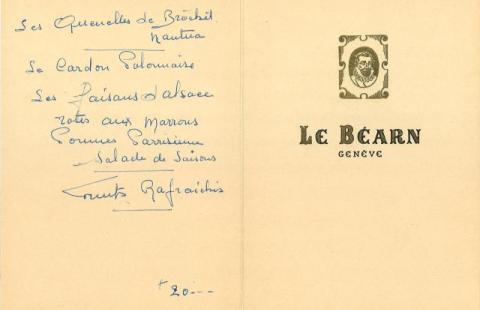

The date on this menu for Wolfgang Pauli’s Nobel…

Know more

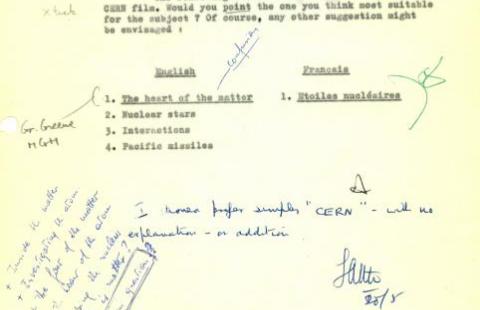

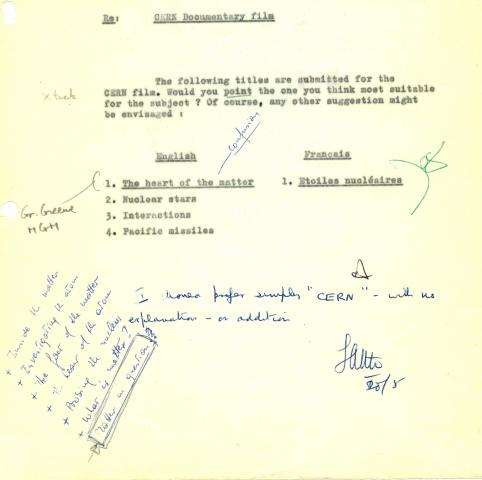

“OERN is difficult to pronounce in most languages”

Has it ever struck you as odd that the initials…

Know more

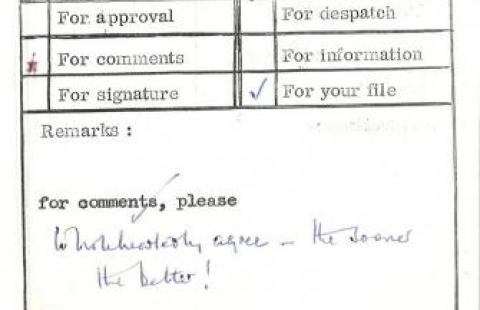

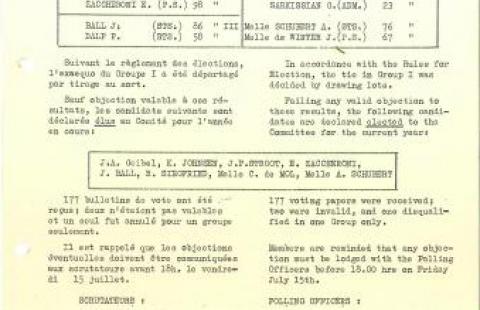

Election of the CERN Staff Association Committee

Voting for the Committee members of CERN’s newly…

Know more

The first circulating beam in the Synchrocyclotron

A log book entry written by Wolfgang Gentner, the…

Know more

Closure of CERN’s Theoretical Study Division in Copenhagen

During the construction of CERN in the 1950s,…

Know more

8th Annual International Conference on High Energy Physics

The 8th Annual International Conference on High…

Know more

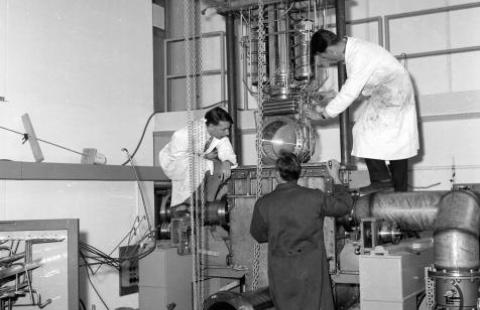

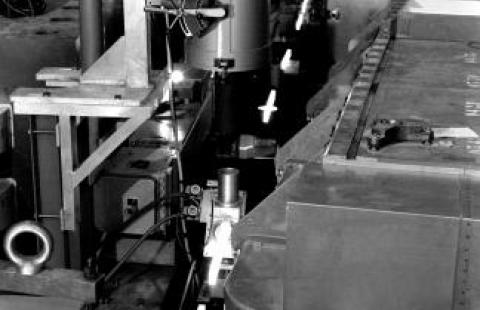

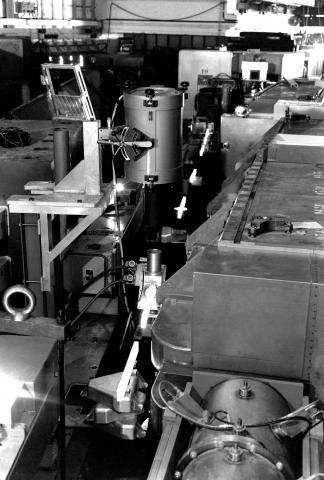

Preparing CERN’s HBC30 bubble chamber for testing

The 30cm liquid hydrogen bubble chamber (HBC30…

Know more

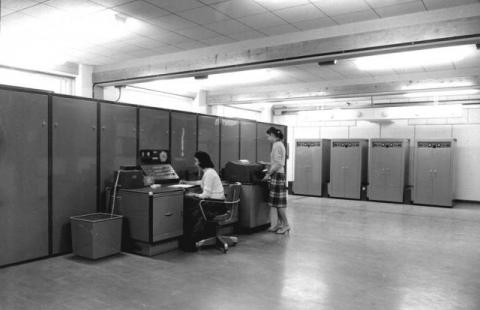

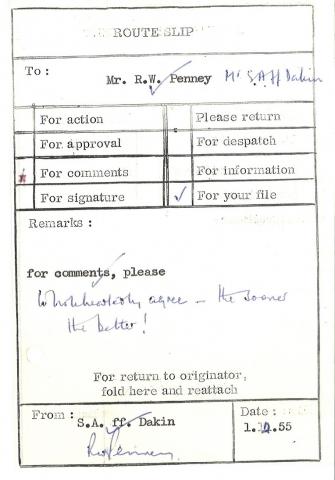

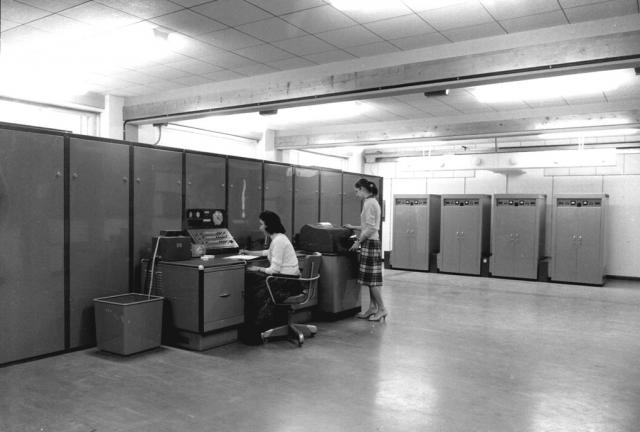

First session of the CERN Computer Users’ Committee

Demand for CERN’s Mercury computer had increased…

Know more

Miss Steel and the Scientific Conference Secretariat

Conferences are a great way to promote…

Know more

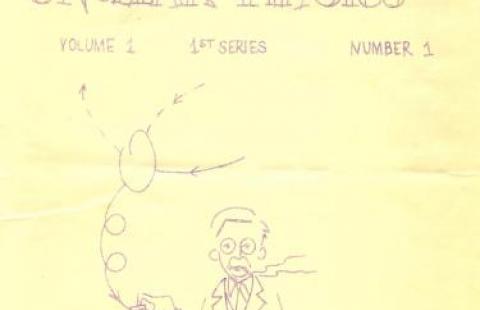

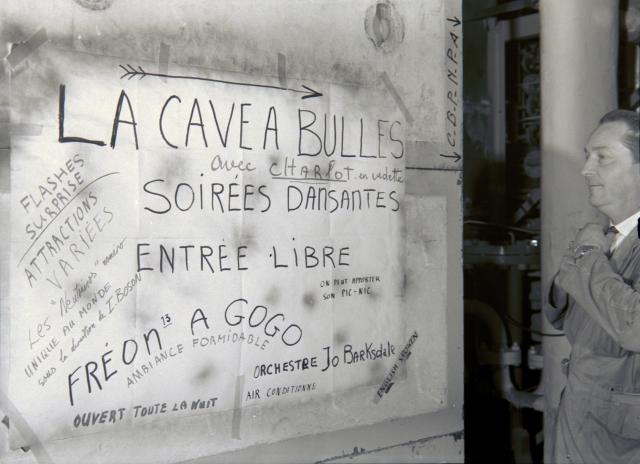

The lighter side of neutrino experiments

A buzz of excitement marked the start of neutrino…

Know more

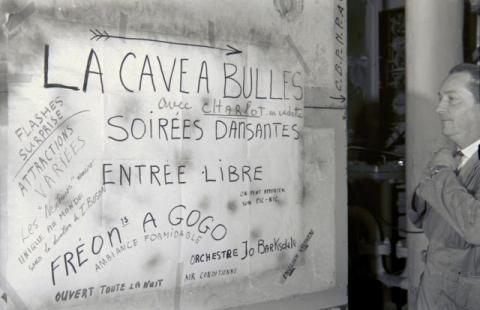

Fun and games at the traditional CERN Christmas party

The tradition of holding a Christmas party for…

Know more

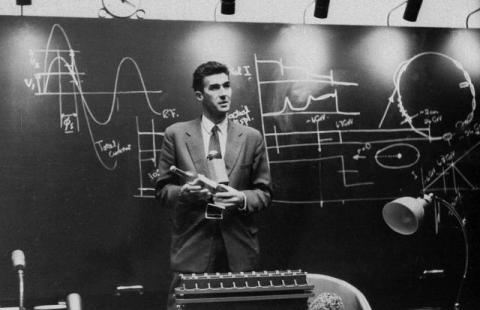

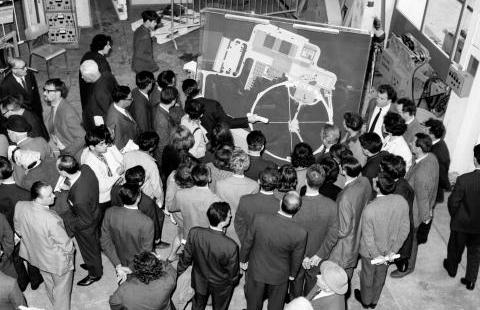

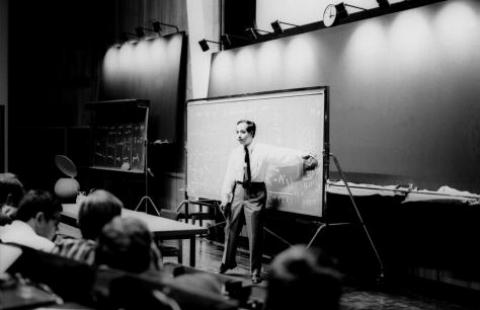

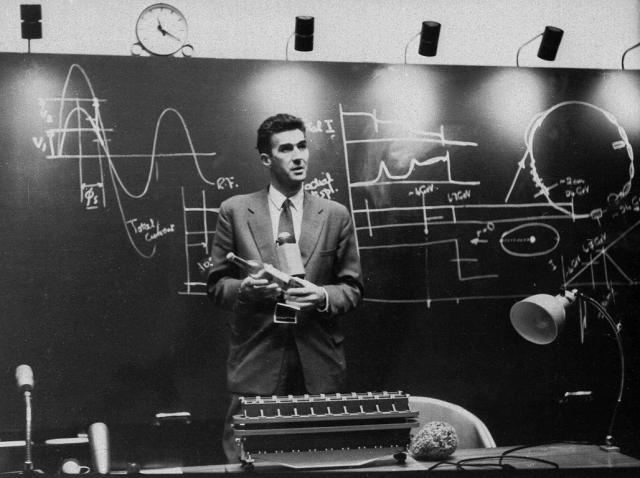

T. D. Lee lectures to CERN’s summer students

Summer at CERN means summer students – and a…

Know more

The world’s first proton-proton collider

The scene is the control room of the Intersecting…

Know more

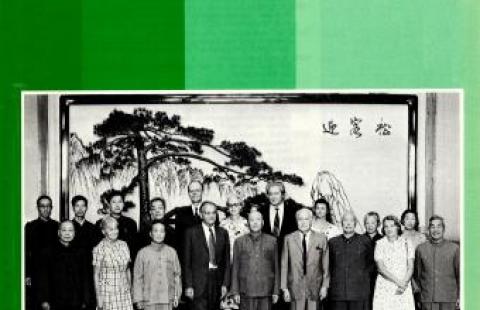

Chatting about physics at the National People’s Congress

A trip to China in September 1975 helped pave the…

Know more

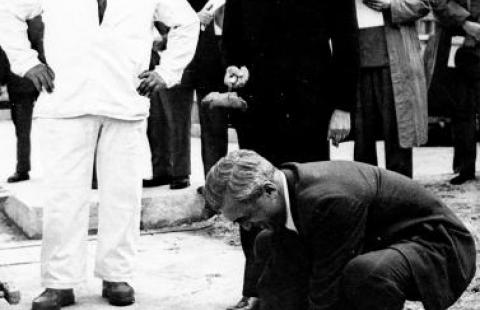

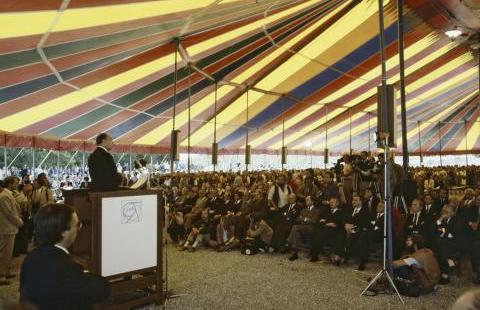

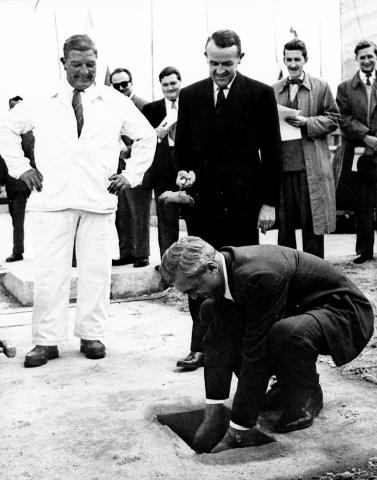

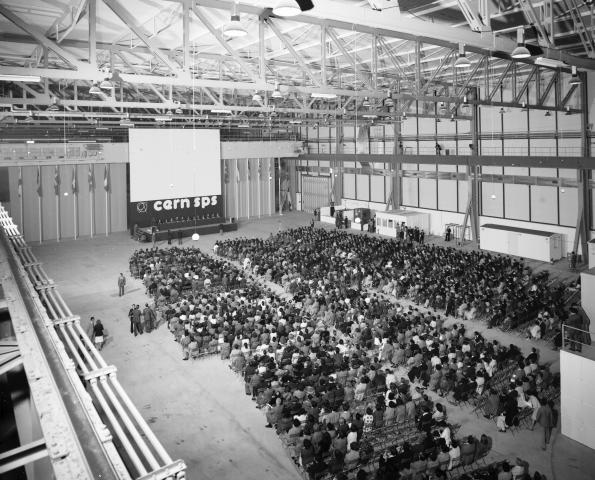

Speeches from the Swiss and French presidents at the LEP ground-breaking ceremony

CERN staff and their families were joined by…

Know more

Embed this timeline

Bertha Pauli’s son Wolfgang is born

Wolfgang Pauli begins his studies in Munich

The Como congress 1927

Wolfgang Pauli appointed professor at ETH Zürich

December 1930 - Pauli’s Neutrino letter (now in music and art!)

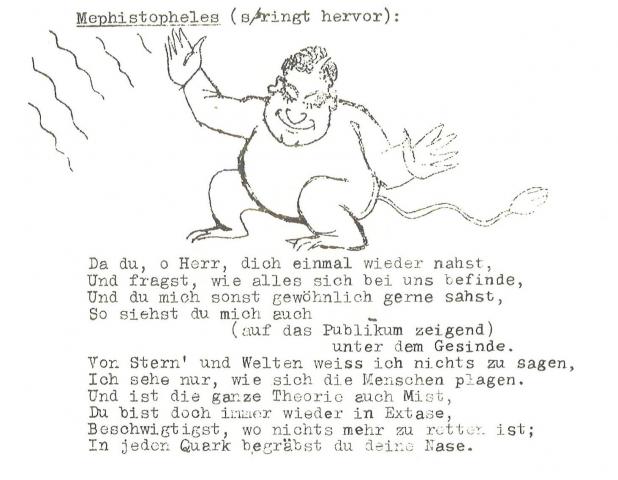

The Copenhagen Faustparodie

Pauli and Sommerfeld in Geneva

Wolfgang Pauli learns that he has been awarded the Nobel prize

Pauli travels to Sweden to receive the Nobel prize

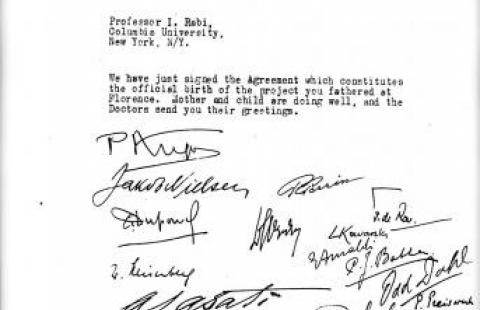

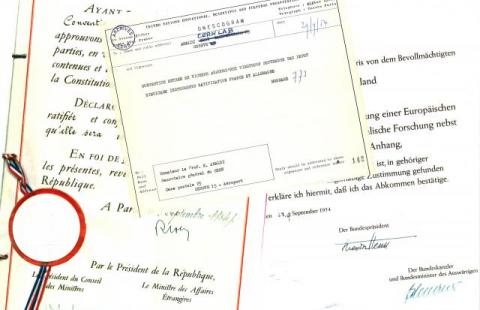

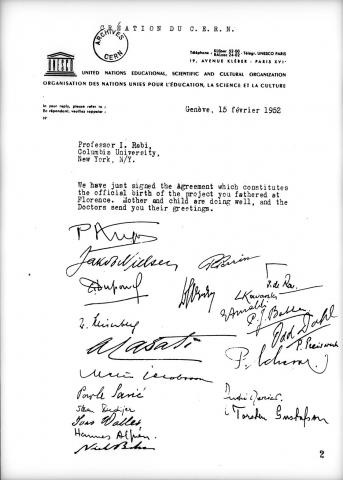

CERN is born, mother and child are doing well

Redesigning the Proton Synchrotron

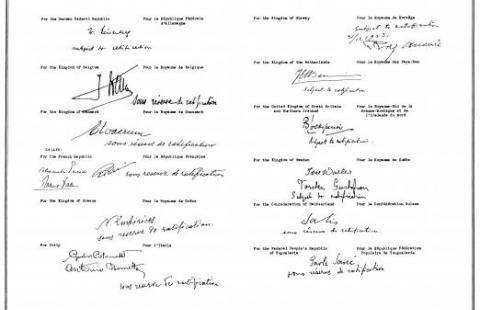

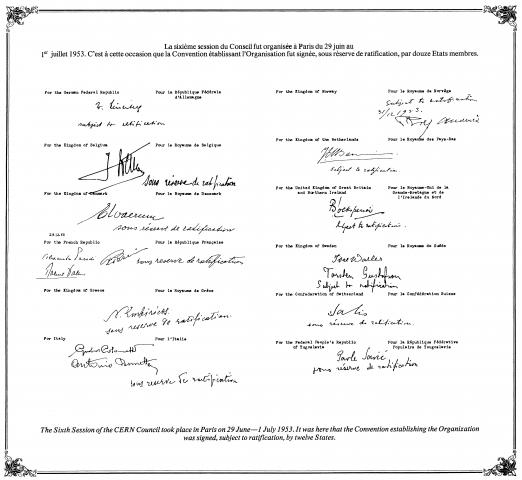

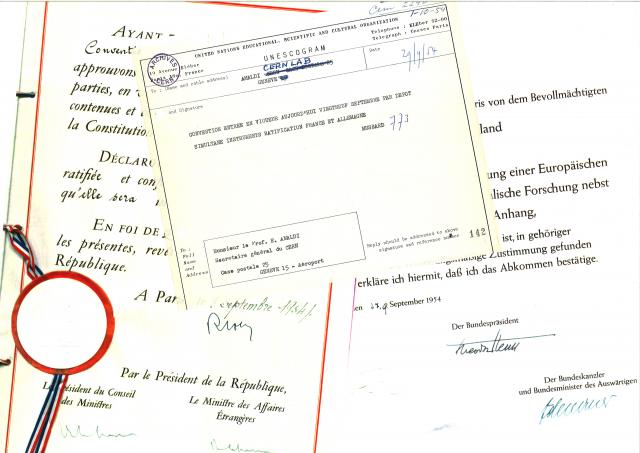

Signing the CERN Convention

Settling into Geneva

Construction of CERN begins

CERN exists!

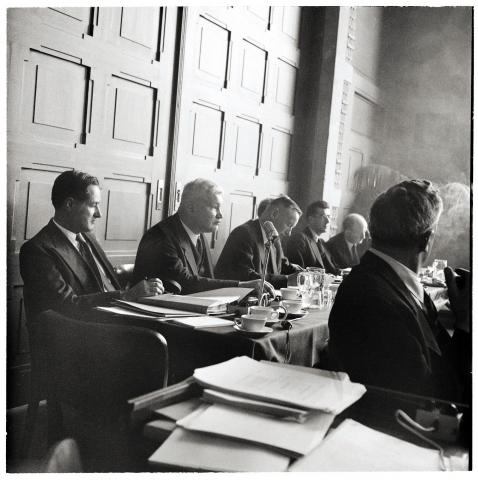

The new CERN Council

“OERN is difficult to pronounce in most languages”

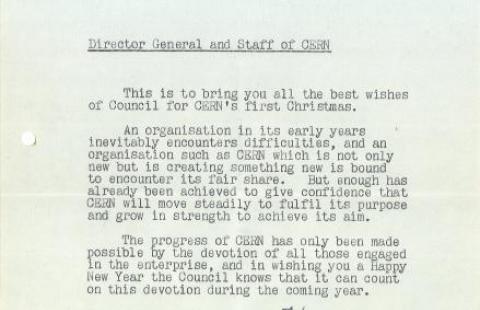

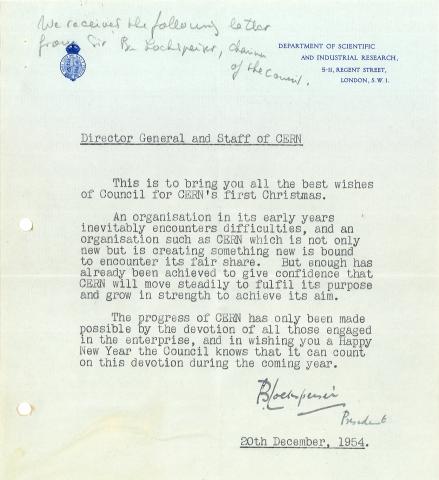

Baby CERN’s first Christmas

Inaugural meeting of the CERN Staff Association

Laying the foundation stone of CERN

Election of the CERN Staff Association Committee

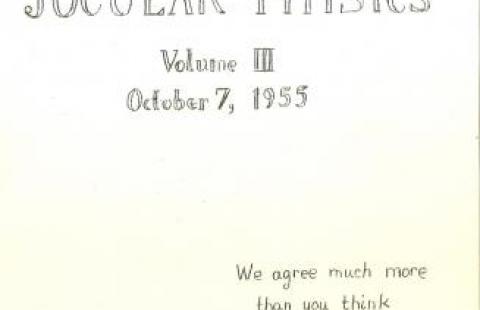

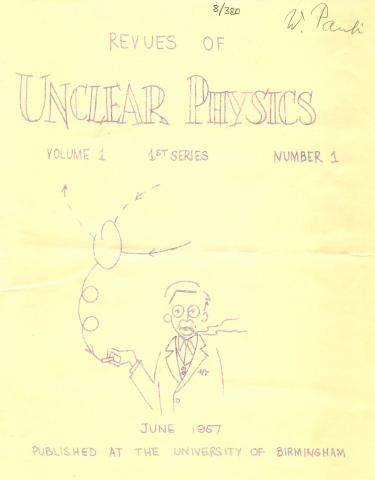

The Journal of Jocular physics 1955

Does CERN need to buy a computer?

Neutrinos detected at last!

Birth of the CERN fire brigade

The P.A.U.L.I. and its uses

The first circulating beam in the Synchrocyclotron

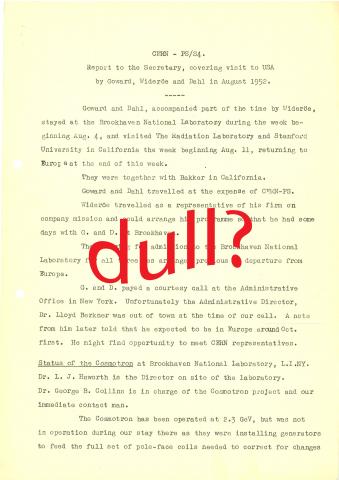

Closure of CERN’s Theoretical Study Division in Copenhagen

8th Annual International Conference on High Energy Physics

Yesterday’s Tomorrow’s World

Preparing CERN’s HBC30 bubble chamber for testing

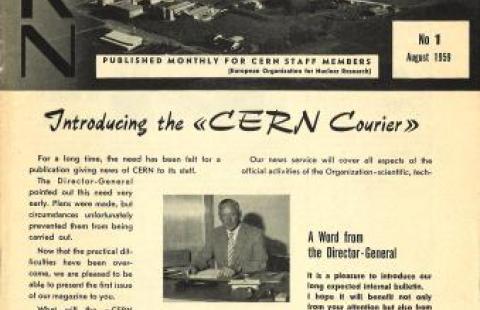

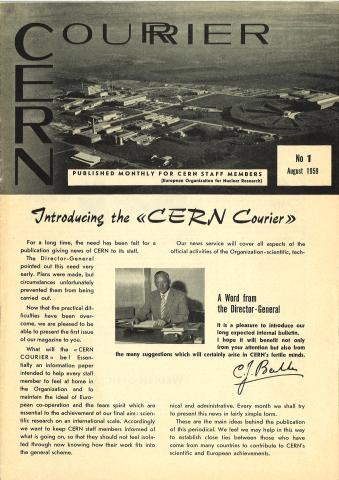

CERN Courier No. 1

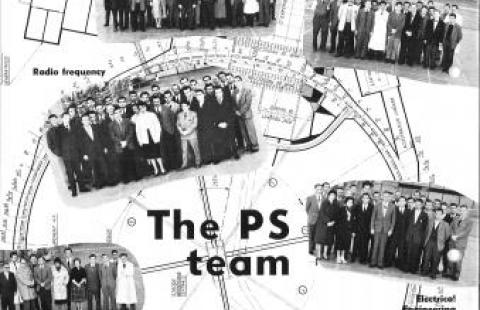

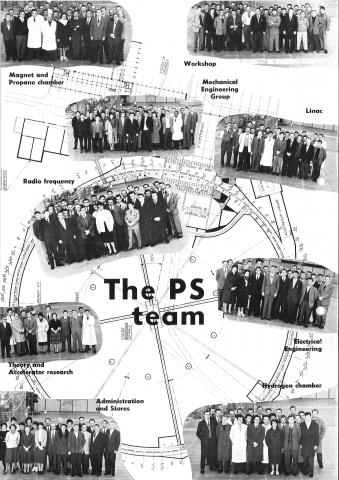

The Proton Synchrotron is up and running

Inauguration of the Proton Synchrotron

First session of the CERN Computer Users’ Committee

CERN commemorates Wolfgang Pauli

Miss Steel and the Scientific Conference Secretariat

Matter in question

Inauguration of the IBM 709

Summoning the Founding Fathers

CERN on ice

The lighter side of neutrino experiments

Fast ejection of protons from the PS

CERN Open Day!

Fun and games at the traditional CERN Christmas party

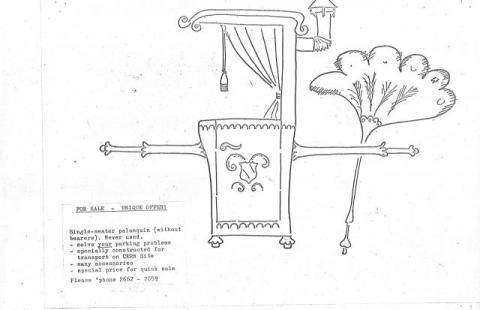

No parking problems with a palanquin

A CERN stamp

Muons are like drunken cowboys

The 55th Tour de France comes to CERN

CERN’s new telephone exchange

T. D. Lee lectures to CERN’s summer students

An Apollo 9 astronaut visits CERN

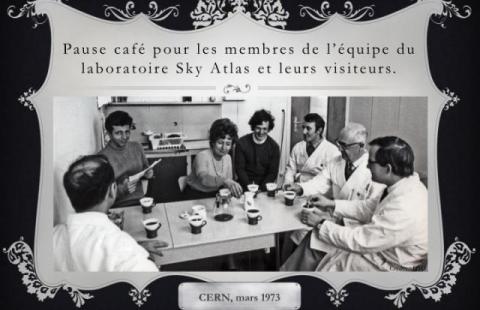

The European Southern Observatory at CERN

The world’s first proton-proton collider

New home for CERN apprentices

Computers: why?

Completion of the SPS tunnel

Chatting about physics at the National People’s Congress

Inaugurating the Super Proton Synchrotron

CERN Staff Day

His Holiness the Dalai Lama visits CERN

Speeches from the Swiss and French presidents at the LEP ground-breaking ceremony

CERN’s 30th anniversary

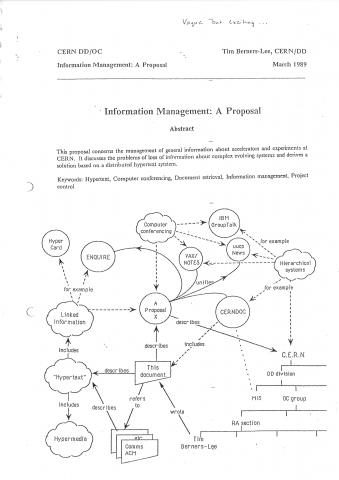

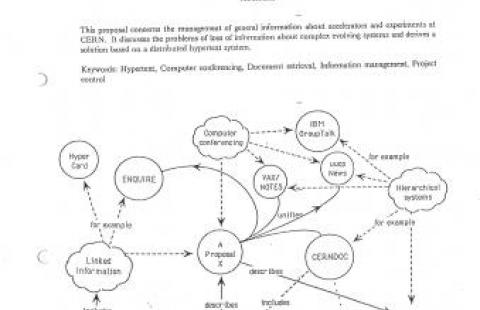

First outline of the World Wide Web